A beautiful article I stumbled upon recently....

A beautiful article I stumbled upon recently....

A MANAGEMENT scholar once remarked that there are as many definitions of strategy as there are writers on the subject. Today, according to Henry Mintzberg, as many as ten major schools of strategy exist. These schools approach strategy from diverse, and sometimes conflicting, perspectives. However, two basic elements permeate all these schools of thought.

The first sees strategy as the `fit' between an organisation and its environment. The second views strategy as goal-directed action. These two notions came close to being challenged in the 1970s, with the advent and development of the "descriptive" approach. Henry Mintzberg, one of its chief protagonists, pointed out that strategies get formed — they cannot be formulated in advance.

Given the impossibility of predicting outcomes, only some elements of an intended strategy get realised, while most fall by the roadside, unrealised. Again, realised strategy includes a component that consists of unintended outcomes — the emergent strategy. According to Mintzberg, strategy involves synthesis and calls for the exercise of judgement and creativity. It cannot be reduced to the analytical task of planning or programming.

Having challenged mainstream thinking in this fashion, scholars who viewed strategy `emergent' did not carry forward their arguments to their logical conclusion.

If strategies are emergent, what use are goals? Quinn sought to answer this riddle by postulating that managers need to be goal-directed, but to reach these goals, they should adopt the approach of logical incrementalism, recasting both the goals and actions in small steps till the appropriate configuration of strategy, structure systems and other organisational attributes they have to achieve become clear.

Recently, a new school of thought based on the theory of complexity challenged the concept of fit, so central to strategic management. This school has advanced an alternative view of strategy in which "co-evolution" replaces the notion of "organisation-environment fit".

In the complexity-based view, organisation-environment relationships are viewed as inter-organisational networks. Organisations co-evolve with other organisations and entities external to them, driven more by their internal forces of "self-organisation" than by the external forces of environmental selection.

While this co-evolution takes an organisation far from equilibrium, the latter stays within a bounded region in parameter space, called the "strange attractor". These strange attractors are emergent and cannot be predicted in advance. The only constant, then, according to this school of thought, is change. Organisations survive and thrive by being in a state termed the edge of chaos — a state of constant flux bordering on the chaotic, but not chaotic. What differentiates this state from a chaotic state of random changes is the fact that the parameters of the organisation, while constantly changing, remain confined to "strange attractors".

Two things are clear from the tenets of complexity theory. First, the task of strategy is not to structure the organisation to achieve the best fit with the environment. The task, instead, is to maintain it at the edge of chaos by ensuring resource modularity and experimenting with ever-new configurations of organisational resources. Second, since outcomes are unpredictable, long-term goal setting would be futile. This calls for repudiating the view of strategy as goal-directed action.

While contemporary strategic management thought has transcended "fit" and equilibrium because of complexity theory, it is yet to go the whole way and repudiate strategy as goal-directed action. Many protagonists of the complexity theory still adhere to goals and predictable outcomes. Thus, while some are concerned with predicting the shape of strange attractors in advance, others are engaged in empirically finding out linkages between the "edge of chaos state" and profits.

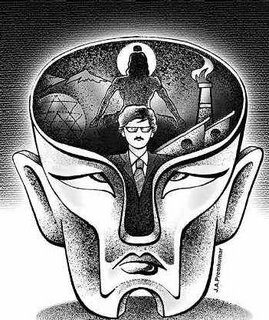

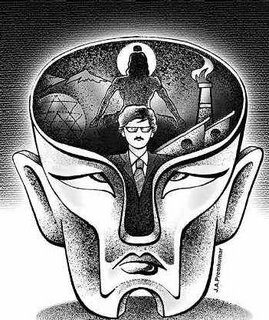

The objective is to somehow arrive at new prescriptions for enhancing goal-attainment. This hesitation to go beyond goal-directed action perhaps stems from the Occidental mindset. One realised this while interacting with an American Jesuit, also an ethics consultant to MNCs. When talking about the Karma theory even the man of religion could not help interjecting, "If goals are not important, what are?" If strategy is not goal-directed, it is not difficult to see that complexity theory is taking strategic management towards a "Karmic" strategy paradigm — strategy as selfless action, as action without regard to its outcome.

Karma Yoga is not only the performance of actions without expectation of reward, but is, in addition, the performance of actions according to the yuga dharma. What is the yuga dharma that can guide organisational actions? Complexity theory points to seeking and achieving ever-new resource combinations as this dharma.

The reader familiar with Schumpeter would readily recognise that this is exactly what entrepreneurship is all about — combining factors of production in new ways. And, by definition, that which is new is not old or previously conceived.

Complexity theory calls for businesses to adopt entrepreneurship than the accumulation of profits as their dharma. Even Karl Marx was not averse to recognising this "revolutionary" side of capitalism, while opposing its other side of greed and aggrandisement.

Just as Vivekananda exhorted the western world to "go back to Christ" years ago, "Go back to being entrepreneurs" is what complexity theory seems to be telling the capitalist world now.

Ironically enough, rewards seek out the karma yogi whose actions are not driven by the expected fruits of his actions. It can be shown that the same is true of the business world. A re-look at corporate success stories would establish this fact.

A detailed examination of the history of Sony would reveal that the secret of its success was not — as Gary Hamel and Prahalad would have us believe — the core competence it deliberately built over years, but its devotion to creating new products as a goal in itself. In today's hyper-competitive environment, expecting businesses to repudiate profits and focus on entrepreneurship instead may sound like expecting a man-eater to turn vegetarian. But the rewards await the vegetarian tigers, not the man-eaters.

And here are a few images from her life in happy times.. (Aren't these like images from our personal lives)....

And here are a few images from her life in happy times.. (Aren't these like images from our personal lives).... With her Father ..

With her Father .. With her friends at party ...

With her friends at party ... In Venezuela on vacation ...

In Venezuela on vacation ... And then in Decemeber 1999... a drunk driver .. 17 year old male student rushing home after a couple of hard packs of bear with his friends ... crashed into her car .. and it destroyed her life for ever ...

And then in Decemeber 1999... a drunk driver .. 17 year old male student rushing home after a couple of hard packs of bear with his friends ... crashed into her car .. and it destroyed her life for ever ... She was caught in the burning ... car for 45 seconds and was badly burnt ... After the accident Jacqueline needed 40 operations .....

She was caught in the burning ... car for 45 seconds and was badly burnt ... After the accident Jacqueline needed 40 operations .....

This is her getting treatment several months after the accident ...

This is her getting treatment several months after the accident ... With her left eyelid she needs eyedrops to keep her vision ...

With her left eyelid she needs eyedrops to keep her vision ... Now 20 years old, the boy who caused the wreck while drunk on that fateful night cannot forgive himself .. He knows he has devastated her life ....

Now 20 years old, the boy who caused the wreck while drunk on that fateful night cannot forgive himself .. He knows he has devastated her life .... This was taken 4 years after the accident ....

This was taken 4 years after the accident ....